Simplicity dazzled

Jean-Christophe Bailly

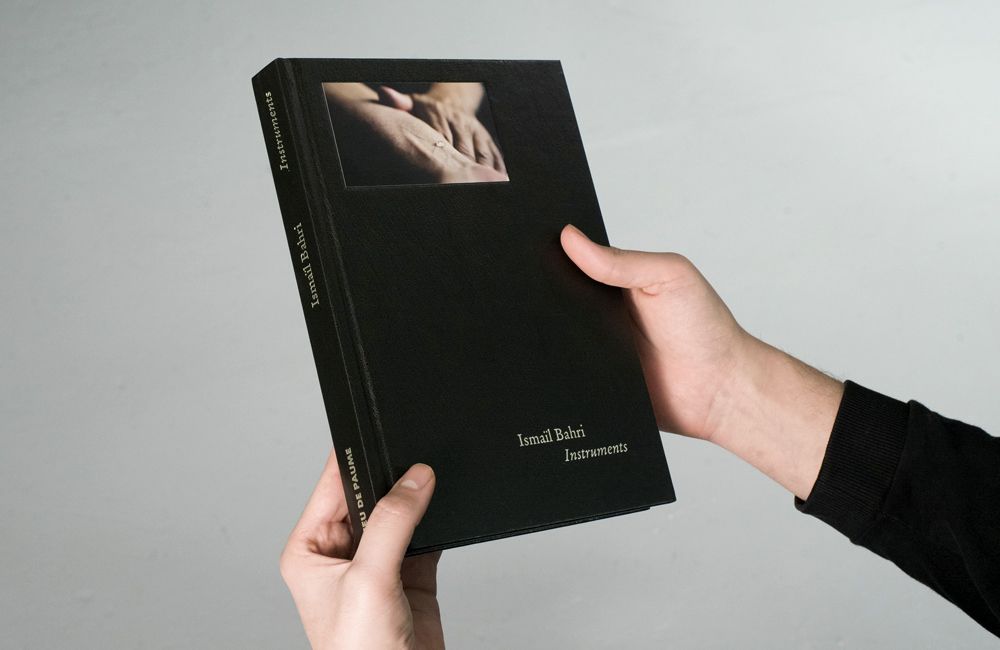

Instruments Catalogue

Jeu de Paume

June 2017

Paris, France

Translated from French by Jeremy Harrison

ISBN : 978-2-915704-68-6

EAN : 9782915704686

Catalogue / pdf / Français / English

Invasion by quantities (of signs, objects, goods, forms, information) is the principal characteristic of modern times. There is nothing new about quantity as such, and neither flow nor mass are a modern invention, but they have gone way over the threshold of anything imaginable. Not like a tsunami, overturning everything in its path, but like a sort of constant, immanent gush soaking into almost all the spaces in which our actions and our thoughts operate. It has always been necessary to create fresh areas and to prise open gaps and spaces to make it possible to get away from the dictates of convention and to reconsider the meaning of actions, their immediate sense and their resonance. But the production of meaning that such (principally artistic) initiatives have made possible has eventually ended up as yet another accumulated layer, thin though it may be. The danger, for these acts of producing sense as well, is one of saturation, and it is all the more dangerous since the quantitative mass is already considerable. This being the case, how can one go against the flow? How can one resist the entropy that comes with further accumulation?

The question has probably never been asked directly in these terms, but it remains true that the most extreme and foundational acts of modern art anticipated it and answered it with subtractions. Following the logic of one plus one plus one, which was somehow the unacknowledged basis of every work of art, Marcel Duchamp’s Readymades and Kazimir Malevich’s White on White substituted the possibility of taking a step back or creating a stasis. A space of pure possibility emerged, which was, at one and the same time, a background, a bearing surface and an abyss. Without that space, which yawned open with the precision of a caesura, it could be claimed that modern art, bereft of its giddy hauteur, would have become nothing more than a decorative frieze. But it actually made little use of the ethical challenge to its primary or ultimate sense, more often than not, proving forgetful in its total absorption in the task. And so it comes as an unexpected delight to see an artistic experiment emerge from the world of the moving image to confront that caesura or to prise it open.

Ismaïl Bahri’s (video) films all involve, ahead of any form or other installation, an operation of suspense that opens up meaning to the effect of its own emergence. He does not use his films in order to remove something or to clear a space or even to take things further, but rather, through very subtle approaches, to define the area of a possible beginning, or, rather, the possibility of any beginning. Something – a meaning – may appear, must appear, but needs to remain in the mode of appearance, or emergence. It needs to exist (to ‘be there’), but without anything other than the occurrence of possibility being admitted to that existence; it has to have duration (the films are records of experience with a duration of between one minute and half an hour) but, during that space of time, it has to maintain the furtive quality of things that keep coming but do not stay. In that ‘being there’, which we are presented with as it comes, no presence is postulated, no cumbersome Dasein claiming its share, there is only the genuine integrity of a passage or a coming, something fundamental which has no primordial or even inherent intention. Every time, there is an experience, every time (even literally) the tenuous thread of a becoming or an unfolding, every time, according to its own intensity, the resonance of this tiny thing through which difference is engaged.

In the face of such discrete existences, one is inevitably reminded of the chôra, as Plato imagined it in the Timaeus – neither support nor surface, but a place for all possible inscriptions – and the way in which the philosopher (and all philosophy after him) was able to use it to dream of a sort of ideal imitation, preceding every figure, in which incipience, by maintaining itself as such, would prevent the realization of the inchoate and remain suspended, not in a state of becoming or as an expectation, but in a perpetual ‘coming’: something which, in spite of happening, would keep being confused with the possibility of its occurrence, determining a mode of existence at once real and without gravity, which would be like a field of absolute immanence, or the beat of an opening.

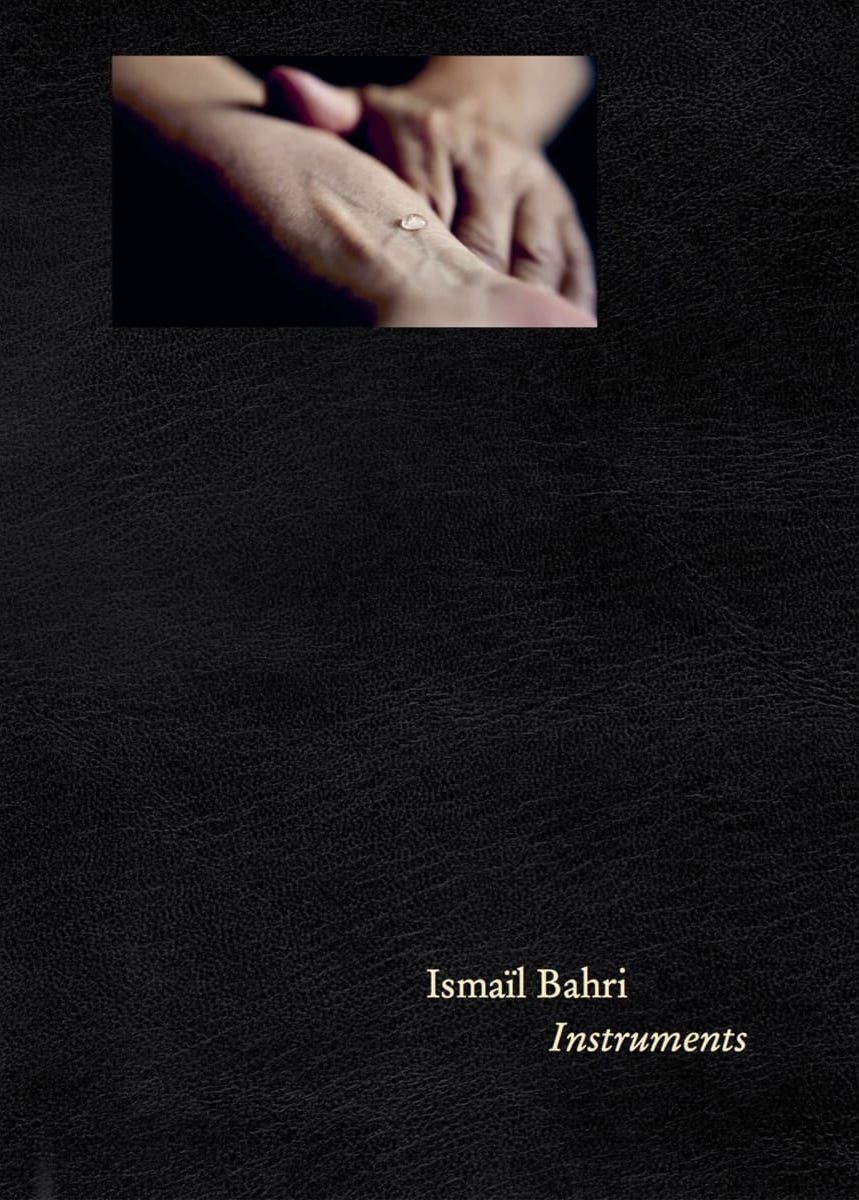

And a beat is exactly what it is: the first video by Ismaïl Bahri that I saw was Line (2011), a minute-long film loop in which one sees a drop of water on someone’s wrist rising and falling to the rhythm of their pulse. It is no more than a pulse made visible. If it had just been about capturing the emotion of this pulsation, which is a pure and simple expression of life seen through the skin, it would have been enough to film the pulse itself on a bare arm. But, transmitted through the drop of water, not only does the pulse become more visible, but what also happens – and we are privy to it – is a transfer: the form of the drop of water (its form and its life-form) is affected – a word that Ismaïl Bahri often uses – by the regular beat lifting the skin on which it is placed. We are involved in something infinitesimal here and in the fragility of the infinitesimal, but that very fragility is like a point which, by dint of rhythmic repetition, eventually turns into a line before our eyes (whence, presumably, the title), a dotted line, which though faint remains obstinately there. This line connecting the points of intensity of the bouncing water drop is only seen when you go up close to the screen; at first it is as if there is no movement at all. What the discovery of movement indicates, because there is movement, is also that one’s own body, by going up close, has taken part in the experience. The experience continues to exist even while it is being displayed. The intention here is not the participatory aspect, but the radical quality of the presentation: what is in progress, what is taking place before our eyes is something evolving, being shown in real time and actually happening in the space where we perceive it.

This amounts to saying that the conceptual dimension of Ismaïl Bahri’s art is not abstract, and that it takes into account the totality of what happens to it. When he exhibited Line in the Chapelle de la Trinité at Cléguérec, in the Morbihan,1 Ismaïl Bahri juxtaposed it with another piece (not a film) entitled Repos (2015), which made visible the action exerted by the surrounding atmosphere on sheets of paper, dyed beforehand by being left for a long time in wine. In this case the slow evolution was the transformation wrought by contact between an ‘affected’ surface, an atmosphere and the lime-coated surface on which the sheets of paper were placed. As he explained at the time, these were perhaps the first steps in an adventure in colour, but, even more, an integral experiment in which the result evolves every day, but nevertheless cannot be known in advance. Although apparently opposed, the temporalities of these two pieces (one minute filmed in a loop, and an action extending over the entire time of the exhibition) came together and gave consistency to an immediate experience of time.

Unfolding – the process of what is taking place, what is in existence and in the process of being formed – is a theme in Ismaïl Bahri’s films. Since the beginnings of film, unwinding and winding have been intrinsically linked to the very idea of film, and our image of time has been enriched by the reference to this spooling effect whereby images fall one by one in a continuous stream. Dénouement (2011) is a complete dismantling of this process, and the deconstruction is elementary and artisanal. What we see, on a white expanse of snow, is a length of black sewing thread jumping about, and one realizes that the reason it is jumping about is because, at the other end, someone is winding it in, not towards themselves, but by coming towards us, because that is where the camera has been placed. The duration of the film is exactly the time taken to wind in the thread, the time it takes for the person doing the winding to reach the camera; the ‘denouement’ is the point where time and the experience stop because there is no longer any distance. In this eight-minute journey, it is as if the thread’s vanishing point had been abolished by its coming towards us. An enormous quantity of thoughts can be extracted from this simple experience. In one sense, it could be said that the drawing (or withdrawing) of the line involves the relationship with space brought about and supported by perspective vision, but it does so only to expand it or abolish it straight away. Instead of having the straightness of a geometrical line, it is the living, trembling, frayed thread of a ball of string being rolled up through the agency of a body in space. This space, which we are shown through the snow-covered expanse, is borderless, apart from the inevitable borders of the frame, and it has the effect of continuously presenting the shot to us as an example of something outside the shot. Ultimately, at each step, so to speak, the act of winding in reduces the distance and, in so doing, embodies what connects distance with temporality: all distance is suspended temporality, and the duration of the film transforms this suspension into a continuum. Like footsteps sinking into the snow, we sink into the thickness of time, which hangs by a thread.

In the ten short videos composing Film (2012) we have a phenomenon of capillarity; it involves long clippings of newsprint gradually unrolling until they end up flat on the surface coated with black ink, on which they had been placed, and to which they are inexorably attracted. Whereas, with the drop of water on the skin of someone’s wrist, it was an interaction between a surface and a volume, Film shows the interaction between two surfaces: not a deposit but a very slow movement that acts as a progression towards a state of stability. What unfolds or unrolls in this way is not an indistinct surface, but printed matter of the world, a triangular clipping from a sheet of newspaper whose characters (calligraphically attractive Arabic) and photos (at one point, a face turned towards us and looking insistently at us), instead of being there already, come, as it were, to meet us, like the ghosts (‘once the bridge was crossed’) in the famous intertitle in Murnau’s Nosferatu. The ink that they are made with joins the ink that receives them, and what we are seeing acts somehow like a birth in reverse. But, once again, we have been confronted with a process and not with its trace or memory. As we watch, the images and words are turned back into ink and, as we watch, the matter of the world that they convey unfolds as it is happening. The loop is well and truly looped.

Latency (2011–2012) is not a video or, if it is, it is like a film made from a succession of stills or, to put it another way, a succession of still forms. Each of the glass plates that make up the piece is the result of a superimposition of layers of milk and white ink and each one, after a delicate manipulation, has reacted differently. It could also be said that each of the forms is, in a way, the photo of the series of micro-events that brought it into being. And again, with these discrete variations, what is involved is an infinity of minute shifts; it is the formal diversity of a series created from identical elements and actions. Each layer behaves differently in relation to the one before it, and the whole set of superimposed states of form acts as a narrative of integrated formation where everything that has come to affect the surface is preserved. In the case of this piece, whose title puns on a lengthening of time and on the milky origin of the matter involved (latence means ‘latency’; milk in French is lait), one could say that ‘becoming’ is trapped in the deferred period when something exists but is not manifest.

Source (2016) is of a completely different order, more basic and much simpler. It is an eight-minute video that shows in its entirety the process of a surface disappearing by being consumed by fire – an ordinary sheet of paper devoured by a hole gradually spreading out from its centre. Here the experimental character does not imply any kind of material or technical trickery, it is simply the phenomenon of combustion, watched, just as every one of us once must have watched it with fascination when we were children. At the beginning, the (white) sheet of paper is intact; then a very small brown hole appears, which immediately widens to form an almost perfect circle that eventually extends to the whole sheet. In a sense, if the sheet of paper is the field of view, it is the field itself that eventually disappears. If it is not sentimental, the emotion that accompanies this inexorable elimination is an allegory of everything that disappears – everything that lives – and it is important to note that, in this case, it is not only the sheet of paper (the field of vision) that disappears: the thing that has affected it – i.e. that small hole widening out and surrounded by a thin red border – exists as a continuously developing form which has, itself, been in the process of disappearing since it began to exist.

The field of vision, and states of the field of vision, occur again in éclipses and Foyer. In these films they are directly related to the quantity of light and the possibility of images appearing. Éclipses (2013) juxtaposes three stiff sheets of paper suspended horizontally in front of a landscape which they conceal. The wind raises them from time to time in a fairly sharp and jerky rhythm that gives furtive glimpses of the landscape they hide. The landscape, alternately hidden and revealed, is the same in each of the three shots, but the framing is different each time. We are by the side of a road running through a desert area, or arid country at least; in one of the shots there is a wall covered with graffiti; we see a motorcycle or a car coming and from time to time a young boy appears. This banal, northern Tunisian landscape is not the background for a narrative; there is no anecdote here. The only visible variations are those imprinted by movements of air on the sheets of paper that act as caches, and this produces a random score from one screen to another. The landscape, which is framed and completely in-shot, switches to being inaccessibly out-of-shot because of its appearances/disappearances. But its concealment is never complete or lasting; we are confronted, here too, with a constant pulsation that acts as a threshold of undecidability. The visible, having lost the calm possibility of being evidence in its own right, turns, as we watch, into a fiction invented by the light.

Foyer (2016), the longest of the videos, sets up something very similar, but the protocol for the experiment is completely different: in place of the éclipses triptych, with its spirited game of hide-and-seek, there is a single shot, and an almost permanent concealment of the visible; all we have are shifts of luminous intensity and increases in the number of shadows flickering on the screen of a sort of blind, but not silent, film. The omnipresent soundtrack gives us the sounds of the city – the background rumble, cars, horns, voices (it is soon apparent that we are in a district of Tunis) – and, above all, the remarks of passers-by who stop and wonder about the camera and its operator, a camera which films nothing but the vagaries of luminous vibration on a sheet of white paper. As the remarks unfold, we become involved in a sort of mirror image of the reality of the shoot, and the successive interruptions (passing film fans, children, suspicious policemen, a group of unemployed youths who bring a Pasolini-like spatter to the proceedings), far from interfering with the image (or absence of image), are like concentric circles of social reality around it – the reality of the moment and the film location. Attention seems to shift at this point, in a simple, radical movement, towards its surroundings. The street becomes a direct extension of the studio and the variations in the light become filters of a kind of improvised assembly. Surprisingly, this avant-garde experience, instead of being isolated or provocative, becomes a ‘focus’ or ‘home’ for the gathering of people through whom the story (the reality experienced by Tunisians) makes its appearance. Foyer, the title of the video, translates as both ‘focus’ and ‘home’. The surface of appearance – ‘the place where everything that can be marked in the world is inscribed’,2 as Derrida said of the Platonic chôra – is not isolated in a laboratory, the world comes to it. And the volatile character of the spoken word, recorded live in the street, gives those marks, which are not printed (even though the exchanges are subtitled), the lightness of an ephemeral passage through existence – at any rate, the complete opposite of all solemnity and pose. A luminous screen flickers and words converge towards it, attracted to it in daylight like moths around a lamp at night, and this shot, although it shows nothing, possesses, nonetheless, an enormously sunny quality.

Orientations, a slightly older video dating from 2010, might appear to be a sort of anticipated recapitulation, insofar as it combines materials that are found separately in other films. This time, it is a stroll in Tunis, and there is also a soundtrack, but it acts as a counterpoint to a continuum of images. What is filmed is not the city itself, but its reflection, as it appears when the very small surface on which it happens – a glass filled with black ink – becomes still. The glass appears at the beginning of the film, and is both actor and narrator throughout. Placed on a wet pavement, it trembles and then settles and begins to function as a reflective surface, which is picked up by somebody’s left hand and carried around the city. Here, too, the experiment is interrupted, or rather complemented, by remarks from passers-by intrigued as to what this man holding a glass in his hand, which he puts down from time to time, can be filming. The alternation of moments of trembling, when the glass moves or when the surface of the liquid is still troubled, and moments when an image may appear, framing what are often quite identifiable fragments of the city within its circle – branches, a wall, a pole, or a sign, for example – quite quickly produces the equivalent of a narrative, not because we are going to be told a story, but because we begin to wait for the image to come; it is like an upward climb followed by a too easily disturbed period of rest. Nothing ever sets in permanently, nothing can set in, and yet what takes place on the portable surface of the glass is like a nod from the absolute. There is no ethereality about what appears, even if it has no duration, and, conversely, no figural draft in the moments when the image is cloudy. The image exists in its entirety as a footstep, suspended in the course of a walk, before walking on. And the state of becoming proceeds with fragments of itself falling away, but then reincorporated.

This alternation between the fixed moments and the natural fade-out of the moments of movement can also be understood as a succession of unrushed passages from photography to cinema and back – the more so, since where we are is the very space where images originated, namely with those images that the ancient Greeks called acheiropoieta (‘made without the hand of man’) and which, wrought by shadows and reflections, were found to be so intriguing. What Ismaïl Bahri suggests is that they continue to intrigue. And they are made from nothing – a glass of ink carried around under the sky, a series of trembling reflections, words exchanged in the street. Someone holds a glass in which there appears an image that is the result of no techne, and was not fashioned by the hand of any man. A digital camera follows in the footsteps of an enquiry that has come down to us from Plato and that takes place, quietly, anxiously, in the streets of Tunis. Everything by Ismaïl Bahri is contained in that dazzled simplicity.