In Ismaïl Bahri's studio at Villa Médicis

Horya Makhlouf

Text for the catalogue A Piu Voci

Villa Médici, French Academy in Rome

June 2024

Link to the exhibition A Piu Voci

There’s a story that those who look for the origin of things love to tell, when it comes to art. It was Pliny the Elder who wrote it down first, many hundreds of years ago, in his Natural History. It offers, as the genesis of the first work of art, an act to which few were witness, of which no one kept a trace, and which could thus easily be established as the ‘first’. The story goes that the daughter of the potter Butades, saddened by her lover’s imminent departure to war, sought to preserve the slightest possible memory of him she could by drawing the outline of his shadow on the wall of her father’s workshop, where they were together for the last time. Hastily, before the shadow projected by the pottery kiln’s flames died down, she sketched the shape of him with a stick of charcoal that fortunately to hand. And thus did the body of that soldier, gone the next day, stay with her a little longer, beyond the departure and the extinguishing of the light; for she reactivated it when the light was lit again. . . and there was art! Born of the desire not to forget, the need to capture what cannot last, the urge to reconstruct what has already disappeared. Pliny’s story retained neither the lovers’ names nor the details of their faces, but that hasn’t stopped the artists who read it from imagining their features. Nor did it prevent that serious story from becoming a solid myth, whereby the nameless daughter of the potter Butades and her shadowy lover have lived happily ever after and had many portraits. With pen, chisel or brush, a good many artists have sought to perpetuate this fine story of love and art.

But what if Pliny got it wrong? What if his story was incomplete? And what if no one had retold it? Where do myths come from, and what makes them endure? Why that girl and that boy, so long ago and in that place? Why has it come to down to us, here and now?

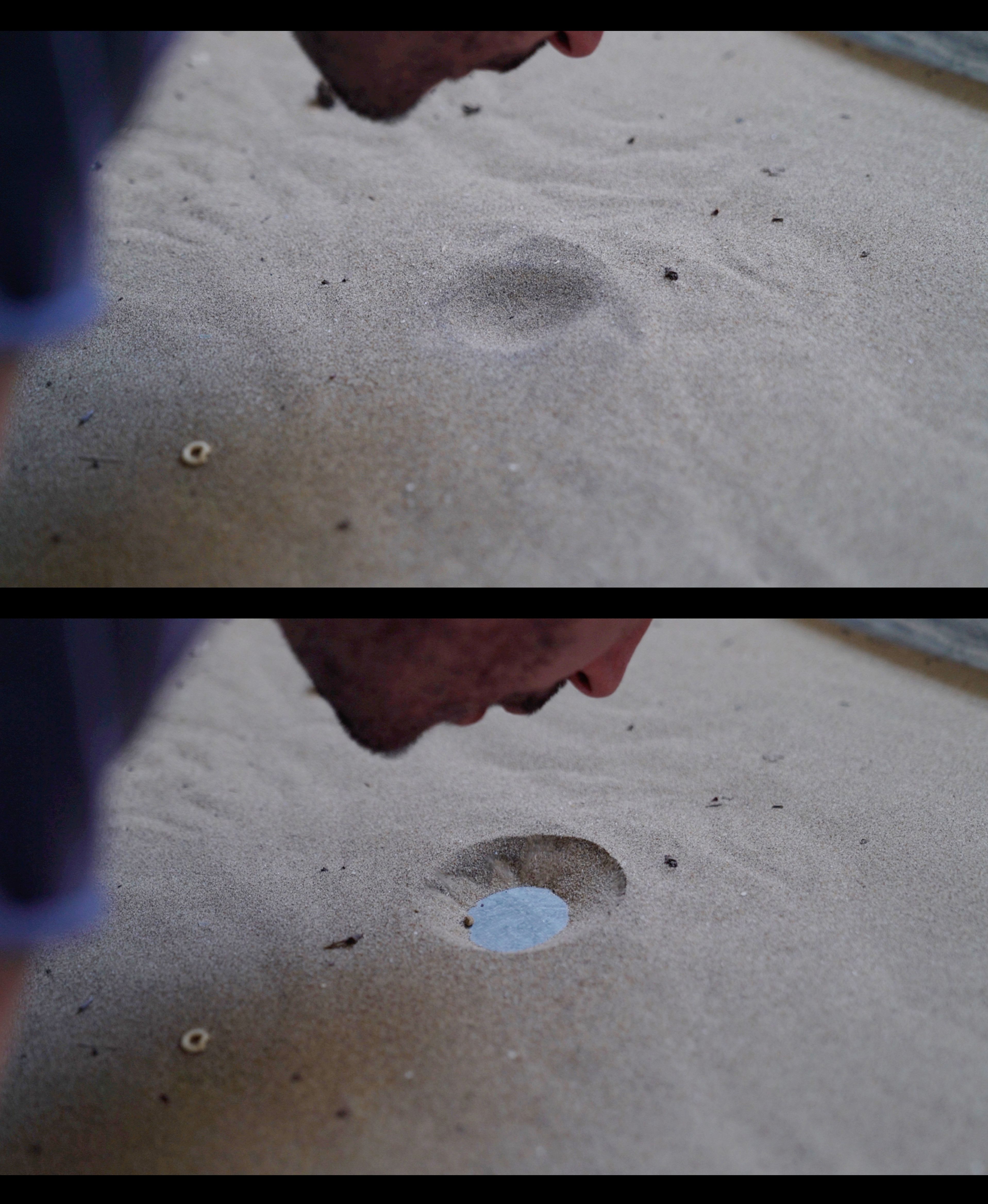

Another beginning to this story might have been when Ismaïl Bahri undertook to measure out his Raoued Beach with rolls of adhesive tape, which fortunately lay to hand in his studio. Or the time when he sought to capture the storm battering some plants he came across in dunes; he found them tracing perfect circles in the sand with the tips of their bent stems as they resisted the wind. Or the time when he found a sweet in his pocket, covered with dust and other particles of life fallen there by chance and in a certain sticky order. Yet another beginning might have been the afternoon when he set out to find the smallest pebble in the garden of the Villa Medici, aided in his impossible quest by residents’ children who happened to be there. Or the day when he discovered the ‘invisible library’ at Herculaneum, which has been carefully preserved since the shifting of ashes from the eruption of Mount Vesuvius, yet without anybody being able to consult it. In glass cases, a whole corpus of books lie, waiting. The lava that destroyed the city so long ago fossilised them and condemned them never more to be opened and read, or else risk crumbling into pieces. What stories, what beginnings and endings, may have been waiting there for centuries to be unrolled?

And what if, buried among them, were the rest of the story told by Pliny the Elder – who died at the foot of the volcano. What if Pliny had told us that the potter Butades’s daughter had not sought so much to trace the shape of her lover but rather the dancing forms projected onto the wall by the flames of her father’s furnace? What if she had found this way of preserving for ever not the only person she once loved, but the moment, the place and the time she spent with him?

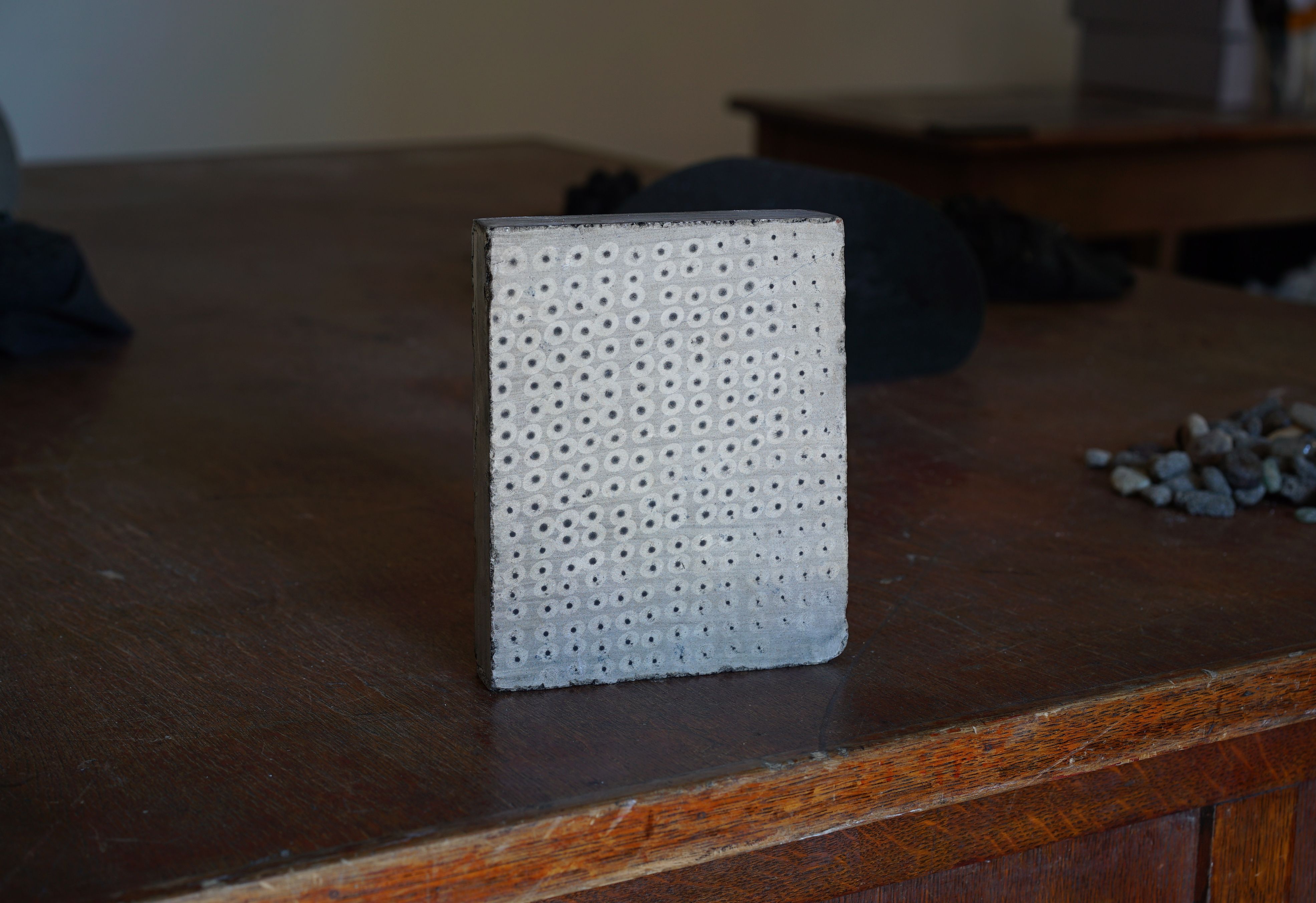

What does history remember of something that happens one day? What does it take for a story to become the one we hold in our memory? Thousands of poetic, scientific, historical or sociological words can be put together to form answers to such profound interrogations, but Bahri prefers mysterious questions, chance experiences and play to bewildering or ready-made answers. There must surely be a place from which to look and take in all of the world’s complexity, grasp all of a narrative’s subtexts, identify the smallest pebble from which the gravel has taken form, the indecipherable letter to which the others attach themselves to make a word, the primordial sound around which a melody is composed. It is not by chance but through effort that this place can be found. So, for some time now, he doesn’t know how long, Bahri has endeavoured to try, repeat, fail, try again, abandon, begin again, atomise, zoom in, move out, probe, collect, tape, bore, pierce, hide, show, catch, capture that which always seems to elude us but is in fact right there. This is the merry, endless quest on which the artist has embarked, in search of the container and ultimate component from which stories and worlds spring, of every thing’s ‘native point’ – as he likes to call it and which he prefers to the notion of ‘origin’, which may say where these things come from but not what they are composed of.

Perhaps this native point is to be found in the rays of sunshine that the artist pinned to the walls of Tunis. Perhaps in the circles of fire that he sought to capture on a piece of paper. In the water droplets that he let run along a wire to form a puddle reflecting the world around it. In the streets of his beloved childhood city that he walked around with his camera, covering it with a piece of white paper so as to capture only the legs, hands, fragments of anonymous bodies, the sounds, laughter and words of wisdom or life lessons proffered by those who were drawn to the strange man with the camera. At La Verrière in Brussels where he spent a few days, perhaps he was split into beams, transmitted through the transparent ceiling and diffracted onto the walls through the cracks and crevices, deliberate or accidental, that appeared during this experience.

Perhaps this ‘native point’ is nowhere and everywhere, whether it has been there forever or only just appeared. This artist who dislikes definitive answers is not one for giddiness either. There are things that cannot be controlled, he learnt from the ancient philosophers Epicurus and Lucretius. To recognise the things that can and those that will always resist, to seek one’s balance between the two and find one’s way forward: this is the path Bahri has chosen to make his way along, whilst he plays. With his little sweet-pebbles and his fossilised rolls of adhesive tape, with his hands and those of companions encountered along the way, he establishes, as rules, the observation of the world and its materiological dimensions, and as objective, the excavation of what is immanent, of what has always been there, just waiting to be observed. In this unending task, the artist, part archaeologist, part alchemist, likes to change the registers of the things distributed at random until it’s impossible to say which one they originally belonged to.

Bahri is pursuing his quest this year at Villa Medici, putting off its completion until later. During his strolls in the gardens of the Villa, he has encountered other residents, a few ghosts, and new native points; he still doesn’t ask where they come from, but how they resonate with the world they compose. Together with the cellist Séverine Ballon, he has composed an enigmatic response. During a slow walk, resembling an embrace of the building, they sound out its soul by running a sewing thread against it. Hand, body and thread bring out the stories and vibrations imprinted on the places where they occurred. The artist who sought to capture the five elements here makes use of the five senses, to activate this new exploration of his endless quest. Perhaps it is enough to listen, taste, touch, feel and look in order to discover the meaning of the world around us.

The charcoal contour drawn by the potter Butades’s daughter outlined not only the shadow of her absent lover but also the cavities of the wall on which it was imprinted, for an instant, the carbon material deposited on its surface, the invisible dust clinging to it, its minuscule pigments, the smoke particles scattered by the wind – which must have swept through it all to keep the fire alight. And what if the point of the drawing was in fact to contain all of that in a stroke. What if it was to serve as the thread sewing all these elements together, the better for them to resonate. In their absence, might the story not be serious enough to be told?